L’identification du cercueil de Joachim Du Bellay sous Notre-Dame est l’occasion d’exhumer des poètes aujourd’hui moins célèbres, que la brigade aristocratique de la Pléiade a contribué à éclipser de la Renaissance francophone par son rejet des « vieilles poésies françaises », « épiceries qui corrompent le goût de notre langue », et le choc de simplification qu’elle a imposé au vers et à la grammaire. Ne nous laissons pas décontenancer par la graphie sauvage de ces poètes chatoyants, on s’y habitue comme à un accent, et ils nous parlent un français vivant et dérégulé.

Joachim (1522-1560), neveu placé du cardinal Jean du Bellay, se découvre tel qu’en lui-même et à sa place au kilomètre zéro sous la cathédrale. Avant de nous intéresser à ses contemporains, oublions un instant qu’il a fait marcher le mètre au pas et enferré la langue française dans ce qui allait devenir son mélange caractéristique de galanterie monotone et de poésie du trait d’esprit, il faudrait en présentant ses respects à cette tombe désormais béante avoir une pensée pour les trésors de fraîcheur permis malgré tout par son style confessionnel et égotique.

ÉPITAPHE D’UN PETIT CHIEN

Dessous ceste motte verte

De lis et roses couverte

Gist le petit Peloton,

De qui le poil foleton

Frisoit d’une toyson blanche

Le doz, le ventre, et la hanche.

Son nez camard, ses gros yeux

Qui n’estoient point chassieux,

Sa longue oreille velue

D’une soyë crespelue,

Sa queue au petit floquet

Semblant un petit bouquet,

Sa gembe gresle, et sa patte

Plus mignarde qu’une chatte

Avec ses petits chattons,

Ses quatre petits tetons,

Ses dentelettes d’ivoyre,

Et la barbelette noyre

De son musequin friand,

Bref tout son maintien riand

Des pieds jusques à la teste,

Digne d’une telle beste,

Méritoient qu’un chien si beau

Eust un plus riche tumbeau.

Son exercice ordinaire

Estoit de japper et braire,

Courir en hault et en bas,

Et faire cent mille esbas,

Tous estranges et farouches,

Et n’avoit guerre qu’aux mousches,

Qui luy faisoient maint torment:

Mais Peloton dextrement

Leur rendoit bien la pareille:

Car se couchant sur l’oreille,

Finement il aguignoit

Quand quelqu’une le poingnoit:

Lors d’une habile soupplesse

Happant la mouche traitresse,

La serroit bien fort dedans,

Faisant accorder ses dens

Au tintin de sa sonnette,

Comme un clavier d’espinette.

Peloton ne caressoi

Si non ceulx qu’il cognoissoit,

Et n’eust pas voulu repaistre

D’autre main que de son maistre

Qu’il alloit tousjours suyvant,

Quelquefois marchoit devant,

Faisant ne sçay quelle feste,

D’un gay branlement de teste.

Peloton tousjours veilloit

Quand son maistre sommeilloit,

Et ne souilloit point sa couche

Du ventre ny de la bouche,

Car sans cesse il gratignoit

Quand ce désir le poingnoit:

Tant fut la petite best

En toutes choses honneste.

Le plus grand mal, ce dict-on,

Que feist nostre Peloton

(Si mal appellé doit estre),

C’estoit d’esveiller son maistre,

Jappant quelquefois la nuict,

Quand il sentoit quelque bruit;

Ou bien le voyant escrire,

Sauter, pour le faire rire,

Sur la table, et trepigner,

Follastrer, et gratigner,

Et faire tumber sa plume,

Comme il avoit de coustume.

Mais quoy? nature ne faict

En ce monde rien parfaict,

Et n’y a chose si belle,

Qui n’ait quelque vice en elle.

Peloton ne mangeoit pas

De la chair à son repas:

Ses viandes plus prisées,

C’estoient miettes brisées,

Que celuy, qui le paissoit

De ses doigts amollissoit:

Aussi sa bouche estoit pleine

Tousjours d’une doulce haleine

Mon dieu quel plaisir c’estoit,

Quand Peloton se grattoit,

Faisant tinter sa sonnette

Avec sa teste folette!

Quel plaisir, quand Peloton

Cheminoit sur un baston,

Ou coifé d’un petit linge,

Assis comme un petit singe,

Se tenoit mignardelet

D’un maintien damoiselet!

Ou sur les pieds de derrière,

Portant la pique guerrière

Marchoit d’un front asseuré,

Avec un pas mesuré!

Ou couché dessus l’eschine,

Avec ne sçay quelle mine

Il contrefaisoit le mort!

Ou quand il couroit si fort,

Qu’il tournoit comme une boule,

Ou un peloton, qui roule!

Bref, le petit Peloton

Sembloit un petit mouton:

Et ne feut onc creature

De si benigne nature.

Las, mais ce doulx passetemps

Ne nous dura pas long temps:

Car la mort ayant envie

Sur l’ayse de nostre vie,

Envoya devers Pluton

Nostre petit Peloton,

Qui maintenant se pourmeine

Parmy ceste umbreuse plaine,

Dont nul ne revient vers nous.

Que mauldictes soyez-vous,

Filandieres de la vie,

D’avoir ainsi par envie

Envoyé devers Pluton

Nostre petit Peloton:

Peloton qui estoit digne

D’estre au ciel un nouveau signe,

Tempérant le Chien cruel

D’un primtemps perpetuel.

Premier sur notre liste, le grand Jean Molinet (1435‒1507). Quoiqu’on ne l’enseigne guère aujourd’hui, Molinet était universellement admiré de ses pairs, et l’anthologie de ses textes FAITZ ET DICTZ DE JEAN MOLINET a été republiée plusieurs fois au 16e siècle. Chroniqueur des ducs de Bourgogne, Molinet représente les derniers feux de la tradition des poètes de cour à la manière féodale, autant que le brasier naissant de la Renaissance franco-flamande, dont il est un acteur aussi important que son ami et collaborateur Johannes Ockeghem. Il était lui-même également musicien et auteur d’œuvres scéniques (passions et mystères) — sa poésie même, d’ailleurs, est faite pour la déclamation, et se décline en chansons, harangues et dialogues.

Molinet fait partie des poètes que le 19e siècle a, avec condescendance, surnommés « les Grands rhétoriqueurs », ces héritiers des formes poétiques médiévales qui en ont poussé le jeu formel et musical jusqu’à l’emballement du moteur. Son ART DE RHÉTORIQUE exalte un véritable bestiaire de formes, « comme lignes doublettes, vers sizains, septains, witains, alexandrins et rime batelee, rime brisiee, rime enchayennee, rime a double queue, et forme de complainte amoureuse, rondeaulx simples d’une, de deux, de trois, de quatre et de cinq sillabes, rondeaux jumeaux et rondeaux doubles, simples virelais, doubles virelais et respons, fatras simples et fatras doubles, balade commune, balade baladant, balade fatrisie, simple lay, lay renforchiét, chant royal, serventois, riqueraque et baguenaude » – de quoi aviver la curiosité de l’Oulipo quatre siècles et demi plus tard.

Car Molinet est amoureux des contraintes et des jeux phoniques, en particulier pour leur potentiel d’ambiguïté et de polysémie. « Qui veult pratiquer la science choisisse plaisants équivoques », écrit-il. Ses poèmes ne se plaisent pas seulement à dissimuler des double-sens, notamment dans un contexte grivois où il tire leur substantifique moelle de mots comme « comporte » et « confesse » — leur force carnavalesque est de faire délirer la production du sens elle-même. Et ils ne s’en affrontent pas moins à leur époque, témoin « Le Testament de la guerre » qui détaille les victimes et les complices des conflits qui dévastent le « povre plat paÿs », ou « La Ressource du petit peuple », sans doute sa vindicte la plus célèbre :

Tranchez, coupez, détranchez, découpez,

Frappez, happez bannières et barons,

Lanchiez, hurtez, balanciez, behourdez,

Quérez, trouvez, conquérez, controuvez,

Cornez, sonnez trompettes et clairons,

Fendez talons, pourfendez orteillons,

Tirez canons, faites grands espourris :

Dedans cent ans vous serez tous pourris.

Non moins sonores sont les énumérations du « Mandement de froidure », dans lequel le roi de la boisson convoque ses troupes, cette fois, pour la débauche de Carnaval :

(…) Hativement a tous vous commandons

Et, comme il faut, aïde vous mandons,

Fremiers de bois, larronceaux et bringans,

Fars papillans, sus le minche fringans,

Pendeurs, traineurs, putiers, houlliers, paillars,

Flatteurs, menteurs, batteurs, rifleurs, pillars,

Marchans de cuyrs, brelenqueurs, orlogeurs,

Bouteus de feu, esgueulleurs, vendengeurs,

Hars parees, barguineurs de caignons,

Faulx crocheteurs, desleaux compaignons,

Escornifleurs de trippes et d’andoulles,

Joindeurs de culz, ratripelleurs de coulles,

Pervers, perjurs, effondreus de toccasses,

Jueurs de dez, combatteurs de ducasses,

Vieux guisterneurs, vieux trompeurs, viés ivrongnes,

Vieux batteleurs, vieux gueux a rouges trongnes,

(…) Goutteux, boitteux, piffres, espoitronnés,

Tricheurs, pippeurs de vie peu prisie,

Ribaux quassés, frappés d’apoprisie,

Cartiers, morveux, sans aleine ne poux,

(…) Et vous trouvés prestz pour livrer bataille

Qui se fera plus de plat que de taille

Entre Baccon et le chasteau Belin,

Pour nous aidier contre ce gobellin,

(…) Car en aïde, avec poix et baccons,

Nous avons bien onze ou douze mil cons :

Cons a detail avons et cons en gros,

Cons a ung blanc et cons a demy gros,

Cons a deux rengs, cons a doubles foeullés,

Cons a manches, cons a doubles oeillés,

Cons a besage et cons a bridelieres,

Cons a maches et cons a grans culieres,

Cons a bourreaux, cons a rouges afficques,

Cons a grands baux et cons a mirlificques… (etc.)

Dans un genre aussi ludique mais plus personnel, finissons sur un fragment de « donat », c’est-à-dire de jeu sur la grammaire latine, en l’occurrence l’occasion pour Molinet de méditer sur le vieillissement à partir de la conjugaison du verbe latin amare.

Je vis le temps que j’estoye verbe,

Les noms et pronoms gouvernoye,

Mais souvent n’avoye ung adverbe,

Par quoy je me determinoye ;

L’adverbe de lieu demandoie,

Ut hic, vel ibi, pour sçavoir

Ou il y avoit quelque proie,

Affin que je la peusse avoir.

Amavi, j’ay amé de faict,

Tellement que c’estoit oultraige,

Mais ce temps preterit, parfait,

Est plus que parfait, veu mon eage ;

Amaveram de bon coraige,

Mais ce train la me samble dur

Pour present et voeul, comme saige,

Laisser amabo le futur.

Notre deuxième specimen : Guillaume Cretin (~1460-1525), contemporain et ami de Jean Molinet, comme lui classé par la postérité parmi lesdits « Grands rhétoriqueurs ». Clément Marot l’appelle dans une dédicace rien moins que « souverain poète français », et dans l’épitaphe pour lui écrite dit de ses œuvres : « Chose éternelle en mort jamais ne tombe, / Et qui ne meurt n’a que faire de tombe ». Chantre de la Sainte-Chapelle, chroniqueur de François Ier, vainqueur de plusieurs puys (concours de poésie), Cretin a joui de toutes les reconnaissances de son vivant. On peinera pourtant à trouver aujourd’hui ses poèmes. Outre les genres obligés de la poésie de cour de forme fixe (chant royal, ballade, etc.), les épîtres en vers — pratique que remet à la mode le goût renaissant de la littérature latine — constituent un pan majeur de œuvre, et c’est par là que nous pouvons l’explorer un peu.

Comme Molinet, Cretin a le goût de « l’équivoque », c’est-à-dire des jeux d’homophonie, poussés par lui peut-être plus loin encore. Mais ici non plus, le jeu langagier n’est pas refermé sur lui-même. L’épître, sous prétexte de donner des nouvelles et d’en prendre, se présente comme une petite chronique qui se déploie dans l’ombre de la grande, celle que Cretin écrit pour le roi. La description qu’il fait à son ami Honorat de la Jaille de la difficulté de poétiser en temps de guerre, en faisant bégayer la rime, touche plus qu’un simple jeu d’esprit :

(…) En divers lieux se font apretz à prest,

Fermans la voie où sont Marchans marchantz,

Cruelle guerre ores aspre és aprestz,

Donc fais larrons estre parchans par champs:

Doulx sons n’en puis mettre en chantz, mais trenchans,

Car l’aigreur rend trop grands debas de bas ;

En chant piteux ne treuve point d’esbas.

(…) Guerre a tousjours Dieu sçait quelle sequelle,

Livres en sont de plainctz & cryz escriptz. (…)

On atteint, dans l’épître qui suit à François Charbonnier, son ami et futur éditeur, des niveaux de virtuosité qui ne facilitent pas la lecture, surtout cinq siècles plus tard : la rime équivoquée est étendue aux premiers hémistiches, produisant des vers quasiment entièrement homophoniques. Avant de rejeter en bloc ces effets comme le feront les poètes de la Pléiade, il faut pourtant prendre la mesure de l’effet qu’ils produisent à la déclamation : un tâtonnement de la langue et de l’oreille qui jette une suspicion absolue, à travers les mots, sur le monde et ses faux-semblants (en l’occurrence, liés à la débauche) :

(…) Quel signe auray de voir cueurs contritz tant

Qu’es si navré, & te vas contristant

Comme s’avant l’effroi ne sçusse pas

Qu’homme sçavant dust souffrir sur ce pas ?

Souffrir, hélas ! quand feu ou souffre irait

S’offrir ès lacz, l’eau claire en souffrirait

Soubz franc courage en souffrette souffrons

Souffrans qu’orage au nez nous blesse au front ?

L’ire des Roys faict or dedans ce livre

Lire defroys, & tour de dance livre

Si oultrageux, que du hault jusqu’à bas

Si oultre à jeux on ne met jus cabatz ;

Doubter dust-on que ne soyons des ans seurs,

D’aster du ton la dance & les danceurs,

Tournay en tour, sa folle oultrecuydance,

Tourney enter, s’affolle oultre qui dance,

Dye au lyepard le sien retour nuant,

Dyaule y ait part que es droict chy tournoyant.

En tes combatz Dame Venus te fache,

Hantes cons bas, & par venuste fache (…)

Pour finir sur une dernière épître un brin plus intelligible, goûtons celle adressée à Macé de Villebresme, collègue courtisan et co-traducteur de poésie italienne, à qui Cretin dit depuis Vincennes tout le bien qu’il pense de Paris (qui est en cette année 1510, de surcroît, en proie aux épidémies) :

(…) Je ronge icy mes croustes & mon lard,

Et je dis bien, pour nous qui aymons l’art

Des orateurs, c’est le lieu plus amene

Qu’oncques trouvay, & qui le mieulx ameine

Mon foible sens à repos d’esperit ;

Tout est tranquille, & rien n’y desperit,

Icy suis hors des durs remords et goustz

Des troux puans, ordes places, esgoustz

Et lieux infectz de l’antisque Lutesse

Dicte a luto, aigre, forte lutte esse

A resister a peste si mortelle :

C’est cas par trop repentin que mort telle.

Icy n’ay poinct le bruit des tumbereaulx,

Je n’oy que vens souffler, & tumber eaux,

Ne n’ay soucy si beuf ou vache arreste

Je n’ay le heurt quand vient ou va charrette,

Je n’ay poinct peur de ses ribleurs de nuict,

Ne du tabut qui tant le monde nuyct (…)

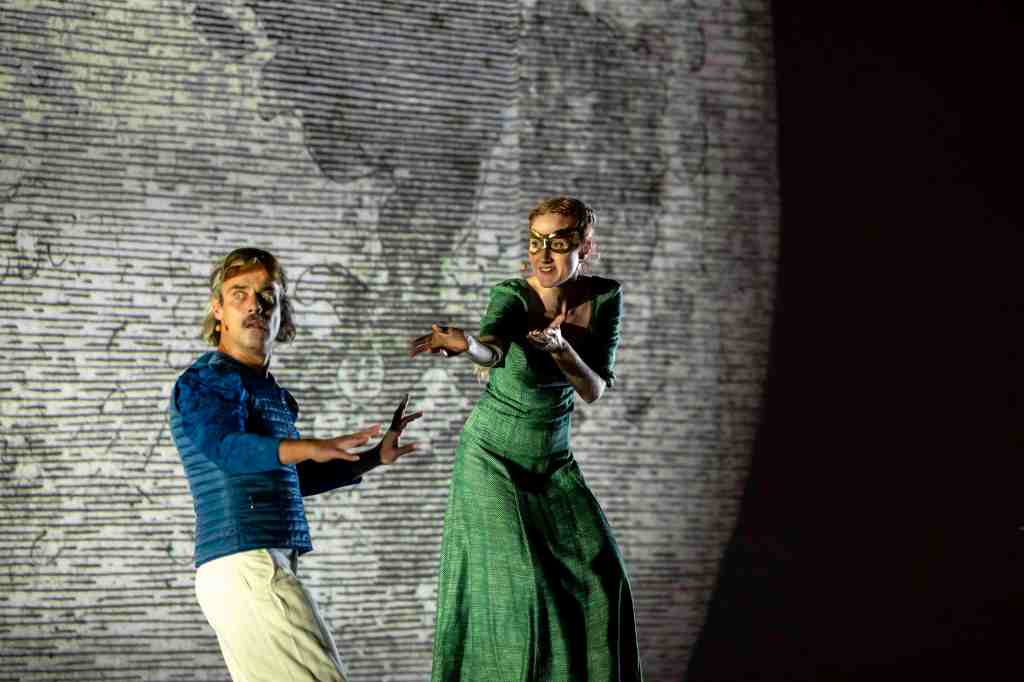

Nous rencontrons maintenant un troisième dit « Grand rhétoriqueur » qui s’est distingué par sa carrière d’homme de théâtre — quoique l’écriture théâtrale n’ait pas été en général inconnue des poètes de l’époque, comme on a pu le voir à propos de Molinet. On connaît parfois le nom de Pierre Gringore (1475-1539) car, en tirant un peu sur les dates, Victor Hugo en a fait, sous le nom de Gringoire, un personnage de son NOTRE-DAME DE PARIS, ce qui le place dans l’imaginaire collectif (nourri des meilleurs tubes de comédie musicale) au « temps des cathédrales ». Mais nous sommes bien au 16e siècle, Luther enseigne à Wittenberg, Érasme publie son ÉLOGE DE LA FOLIE à Paris, le royaume de France se centralise, on traite avec les Borgia et avec Charles Quint, la poésie s’imprime — mais elle se dit aussi sur les tréteaux, dans les rues où l’on célèbre effectivement la Fête des Fous que fantasmera Hugo, la France ne connaît pas ses frontières actuelles, la cour du roi, une parmi d’autres, est à Blois et non à Fontainebleau, et encore moins à Paris ou Versailles. Le récit rétrospectif d’une séparation claire entre les ères est une fiction qui appauvrit notre compréhension de l’époque.

De même, contre une idée des spectacles de rue anarchiques et anarchistes, il faut imaginer un univers théâtral structuré, régenté, surveillé, même s’il est plein de truculente irrévérence et se déploie en plein air, en l’occurrence aux mains des étudiants de la confrérie des Enfants-sans-souci, qui jouent un répertoire satirique : sotties, moralités et farces. Voilà l’arène de Gringore, qui écrit des pièces et endosse le personnage de Mère Sotte — personnage carnavalesque sans doute, mais explicite dans ses commentaires d’actualité et de société, et à la merci d’où souffle vent politique du moment. Gringore est également l’auteur-metteur en scène de tableaux vivants connus sous le nom de mystères. Sa veine satirique est au service des puissants dont il convoitait le patronage (le roi contre le pape, et contre les hérésies qui montent), et fait appel aux outils rhétoriques brillants que l’on connaît à ses contemporains comme Molinet et Cretin. Gringore finira sa vie écrivain pensionné à la cour du duc de Lorraine. Mais ce n’est sans doute pas pour rien qu’on retient de lui surtout l’image chamarrée du saltimbanque, auteur de « crys » servant à haranguer le public sur les marchés, comme celui-ci :

Sotz lunatiques, Sotz estourdis, Sotz sages,

Sotz de villes, de chasteaulx, de villages ;

Sotz rassotéz, Sotz nyais, Sotz subtilz,

Sotz amoureux, Sotz privéz, Sotz sauvages,

Sotz vieux, nouveaux, et Sotz de toutes âges,

Sotz barbares, estranges et gentilz,

Sotz raisonnables, Sotz pervers, Sotz rétifz :

Vostre Prince, sans nulles intervalles,

Le mardy gras, jouera ses jeux aux Halles. (…)

Pour autant, Gringore a également fait carrière de poète publié, et même fait carrière par la publication, faisant partie des premiers poètes et dramaturges qui ont pris en main l’imprimé comme canal de diffusion et source de revenu. Et inversement, l’aspect oral, carnavalesque de son usage des jeux phoniques éclaire ce qui, chez lesdits « Rhétoriqueurs » de papier, peut sembler pur jeu intellectuel si on ne le perçoit pas dans le contexte d’une poésie largement oralisée, scénique, fêtarde — quoique inquiète.

Pour en finir avec ce qui n’est pas une école, mais comme nous le voyons plutôt un continuum littéraire, rendons hommage à un dernier « rhétoriqueur », André de La Vigne (1470-1526), chroniqueur de François Ier comme Cretin, mais aussi dramaturge et pamphlétaire comme Gringore, traducteur comme le sont tous ces poètes, avec cette énumération agressive d’un style que ressusciteront les zutistes et les surréalistes, sans parler des diss tracks des rappeurs :

O Atropos, pluthonique, scabreuse,

Furie aride, sulphurinée, umbreuse,

Fière boucquine, bugle, cerbère, cabre,

Beste barbare, rapace, tenebreuse,

Gloute celindre, cocodrillde vibreuse,

Chymère amère, megerin candalabre,

Arpie austère, cheziphonie alabre,

Gargarineux, steril, colubrin abre,

Lac cochitif, comblé de pleurs et plains,

Palut boueux, vil, acheronic mabre,

Lubre matrone du cru tartarin flabre,

J’ay juste cause se de toi je me plains.

Nous ne pouvions pas esquisser ce panorama sans évoquer une célébrité, Clément Marot (1496-1544), dont le statut canonique de réformateur est amplifié par son statut de fils de Jean Marot, « rhétoriqueur » emblématique de l’ancienne manière, dont l’héritage serait dans le siècle nouveau sursumé. La postérité réduit ainsi souvent (en croyant l’élever) Clément à un rôle de précurseur de la Pléiade et de « l’élégant badinage » vanté par Boileau au siècle suivant. Sa verve vient pourtant directement de la précédente pratique — et à l’âge où les écrivains s’organisent aussi en ce qu’on appellerait aujourd’hui un « monde de l’édition », il est notamment éditeur de Marot père et de Villon.

Littéralement né dans le milieu des cours où les poètes trouvent encore leur emploi, Clément hérite de son père une culture mais aussi une charge au service de François Ier. Il pratique comme ses aînés les formes classiques du rondeau et de la ballade, cultive « l’équivoque » homophonique, et si transition il y a, elle est encore une fois en pente douce : en s’appropriant le genre de l’épître en vers, Clément se pose davantage en sujet singulier, qui parle en son nom propre au-delà des figures imposées. On aurait mauvaise grâce à séparer des « Rhétoriqueurs » celui qui écrit, dans sa « Petite Epistre au Roy » :

En m’esbatant je faiz Rondeaux en rime,

Et en rimant bien souvent je m’enrime [= enrhume] :

Brief, c’est pitié d’entre nous Rimailleurs,

Car vous trouvez assez de rime ailleurs,

Et quand vous plaist, mieulx que moy, rimassez,

Des biens avez, et de la rime assez. (…)

(Chaque rime est composée sur un terme dérivé de « rime », évidemment.) Et si Marot introduit la mode du sonnet à la Pétrarque — qu’il traduit — et celle du genre du « blason » (la fixation-variation virtuose sur un détail anatomique du corps aimé) ce n’est pas simplement par imitation du goût italien, mais aussi en ce que celui-ci fait signe vers la mémoire culturelle médiévale.

Marot avait par ailleurs, comme ses aînés, l’intelligence des échanges avec les compositeurs, dont les mises en musique ont beaucoup fait pour la diffusion de sa poésie, de Clément Janequin et Claudin de Sermisy à Roland de Lassus à la génération suivante. Ses chansons paraissent dans le recueil musical de Pierre Attaignant (inaugurateur de l’édition musicale en 1528) avant même que d’être publiées au livre. Il n’y a pas encore, chez lui, le goût de la simplification radicale, le refus des jeux phoniques expressifs, le systématisme du vers long qui se rapproche de la prose, qui entraîneront le divorce entre les créations poétique et musicale.

Comme tous les poètes du Moyen-Âge, Marot est traducteur, et comme chez eux ce travail-là est une force de renouvellement au moins aussi importante que toute supposée « invention » (au sens contemporain, amnésique de la signification latine d’invenire : trouver, qui a donné aussi troubadour). Chez lui cependant la traduction comme projet prend une dimension particulièrement existentielle : ses traductions des psaumes (à partir des années 1530), reflets de ses convictions luthériennes et mémoire des calamités qu’elles lui ont valu, sont des œuvres poétiques originales, conçues pour le chant, et entrées comme telles au répertoire des protestants francophones (complétées plus tard par Théodore de Bèze). Ainsi la détresse et la claudication du psaume 38 dans cette version hétérométrique :

Las, en ta fureur aigue

Ne m’argue

De mon faict, Dieu tout puissant:

Ton ardeur ung peu retire,

N’en ton ire

Ne me punys languissant.

Car tes flesches descochées

Sont fischées

Bien fort en moy sans mentir:

Et as voulu (dont j’endure)

Ta main dure

Dessus moy appesantir.

Je n’ay sur moy chair ne veine

Qui soit saine,

Par l’ire en quoy je t’ay mys:

Mes os n’ont de repos ferme

Jour ne terme,

Par les maulx que j’ay commys.

Car les peines de mes faultes

Sont si haultes

Qu’elles surmontent mon chef:

Ce m’est ung faix importable

Qui m’accable,

Tant croist sur moy ce meschef.

Mes cicatrices puantes

Sont fluantes

De sang de corruption:

Las, par ma folle sottie

M’est sortie

Toute ceste infection.

Tant me faict mon mal la guerre,

Que vers terre

Suis courbé totallement:

Avec triste, et noyre mine

Je chemine

Tout en pleurs journellement.

(…) Je le dy, et si t’en prie

Qu’on ne rie

De mon malheureux esmoy:

Car des qu’ung peu mon pied glisse,

Leur malice

S’esjouyt du mal de moy.

Vien doncq, car je suis en voye

Qu’on me voye

Clocher trop honteusement:

Pource que la grand’ destresse

Qui m’oppresse

Me poursuyt incessamment.

Las apart moy, avec honte,

Je racompte

Mon trop inique forfaict,

Je resve, je me tourmente,

Je lamente

Pour le peché que j’ay faict.

Et tandis mes adversaires,

Et contraires,

Sont vifs, et fortifiés:

Ceulx, qui m’ont sans cause aulcune

En rancune,

Sont creuz, et multipliés.

Touts encontre moy se bandent,

Et me rendent

Pour le bien, l’iniquité:

Et de leur hayne la source,

Ce fut pource

Que je suivoye equié.

Seigneur Dieu ne m’abandonne,

Deschassé d’ung chascun.

Loing de moy la grâce tienne

Ne se tienne,

D’ailleurs n’ay espoir aulcun.

Vien, et approche toy doncques,

Vien, si oncques

De tes enfants te chalut:

De me secourir te haste:

Je me gaste,

Seigneur Dieu de mon salut.

De Clément Marot, nous ne passerons pas à Ronsard ou Du Bellay, mais à un poète plus curieux et moins politicien, celui que Marot a désigné vainqueur de son concours de « blasons » en 1536 : Maurice Scève (~1501-1564), habile chantre du sourcil.

Sourcil tractif en vouste fleschissant

Trop plus qu’hebene, ou Jayet noircissant.

Hault forgeté pour umbrager les yeulx

Quand ilz font signe, ou de mort ou de mieulx.

Sourcil qui rend paoureux les plus hardis

Et courageux les plus accouardis.

Sourcil qui faict l’air clair, obscur soubdain,

Quand il froncist par yre, ou par desdain (…)

Scève se distingue de la Pléiade, mais aussi d’aînés comme Marot ou Gringore, notamment par une invisibilité volontaire. Ses recueils sont publiés sans nom d’auteur et se dispensent de préface, et sa poésie est avare d’informations biographiques. Bourgeois et non aristocrate, mais ne dépendant pas de l’écriture pour vivre, il n’y a chez lui rien de cette mise en scène par soi-même du poète à fins de marketing qui donnera lieu au statut moderne de l’Auteur, mais pure orfèvrerie verbale. On le sait pourtant au cœur d’un cercle lettré lyonnais, ville de livres et d’influences culturelles mêlées — cependant, nous ignorerons probablement à jamais par exemple son rôle exact, sans doute considérable, dans les activités de son éditeur, le prolifique Jean de Tournes, et même l’étendue complète de son œuvre.

Comme Marot, Scève absorbe à grandes gorgées l’influence de Pétrarque, laquelle fera aussi à travers la mode du sonnet la fortune de la Pléiade. Mais Scève ne succombe pas à l’homogénéisation littéraire qui caractérise ce que le Classicisme voudra retenir du siècle, et entremêle l’inspiration méridionale à la dextérité des « Rhétoriqueurs ». Sa manière la plus célèbre fait revivre en la variant la configuration courtoise (dans sa version pétrarquisante tourmentée) dans DÉLIE, recueil cryptique orné d’étranges emblèmes gravés, dédié à l’impossible aimée éponyme. Qu’on en juge par un des 449 dizains qui composent ce recueil comme autant de carrés de texte posés sur les pages, jouant ici de la symétrie jusqu’à la confusion :

En toi je vis, où que tu sois absente :

En moi je meurs, où que soye présent.

Tant loin sois-tu, toujours tu es présente :

Pour près que soye, encore suis-je absent.

Et si nature outragée se sent

De me voir vivre en toi trop plus qu’en moi :

Le haut pouvoir qui, oeuvrant sans émoi,

Infuse l’âme en ce mien corps passible,

La prévoyant sans son essence en soi,

En toi l’étend comme en son plus possible.

Compressée dans une forme dense qui force la contorsion de la syntaxe (forme héritée de la ballade médiévale, dont la strophe carrée est l’unité de base selon Molinet), la langue élastique de l’époque est désormais moins prolixe, concentrée qu’elle est sur les antithèses caractéristiques de la symptomologie amoureuse de Pétrarque. Ainsi retrouve-t-on chez lui l’hermaphrodite, image platonicienne de l’idéale fusion du masculin et du féminin, ou encore les opposés classiques chaud/froid, évoqués par exemple sous la figure de l’antipéristase, c’est-à-dire leur augmentation mutuelle — non content de caser un tel terme au dernier vers d’un poème, Scève le fait rimer avec extase :

(…) Et quant a moy, qui sçay qu’il ne luy chault

Si je suis vif ou mort ou en estase,

Il me suffit pour elle en froit & chault

Souffrir heureux doulce antiperistase.

La quête, on le devine, n’est pas simplement amoureuse au sens terrestre, et le sujet poétique compare son esprit torturé à un Prométhée dévoré que l’espoir fait « au mal renaistre incessamment ». Délie est par anagramme L’Idée, et si le poète traque l’idée fixe dans une forme obsessive-compulsive et malgré tout charnelle, sensorielle, l’hermétisme de Scève suggère des attentes alchimique vis-à-vis du brasier amoureux transfigurateur : amour-lab-oratoire. Et de fait Scève est aussi l’auteur du poème épique MICROCOSME (1562), où l’écriture comprimée de DÉLIE se libère en 3003 vers exaltant la beauté du cosmos et la connaissance scientifique. Restons sur un extrait de cette poésie unique dans son genre :

De poinct, ligne, cerne, angle, en divers corps formés

Mesure la figure aux traits theoremés

A disproportion pour se prospectiver,

Comme par contrepoints à Musique arriver :

Musique, accent des cieux, plaisante symfonie

Par contraires aspects formant son harmonie :

Don de Nature amie à soulager à maints

Voire à tous, nos labeurs, & nos travaux humains.

Qui par l’esprit de l’air, noeu du corps, & de l’ame,

Le sens à soy ravit, & le courage enflamme :

Et par son doux concent non seulement vocale,

Mais les Demons encor appaise instrumentale,

Comme au Prophete saint l’esprit divin excite

Par le Harpeur sonnant le futur, qu’il recite,

Promettant s’accointer par melodieux sons

Terrestres animaux, & marineux poissons :

En guerre s’animer, & obtenant victoire

Par hymnes, & chansons rendre au Toutpuissant gloire.

Louable faculte du sens, & de raison

Differentant les tons par la comparaison

Des graves aux agus en nombre mesuree

Monstrant speculative, & chantant figuree.

Dans l’école dite lyonnaise, c’est-à-dire le cercle de Maurice Scève que nous avons précédemment évoqué, on ne peut rester sans mentionner une rare figure un peu fameuse, celle de Louise Labé (~1523-1566). La particularité de ce cercle-là a été le nombre de femmes qui en ont fait partie — un des points par lesquels il se démarque du men’s club de la Pléiade — et Labé se distingue à travers cette singularité-là aussi, en plus d’être une des voix poétiques les plus intéressantes tous genres confondus, par la seule force des trois élégies et vingt-quatre sonnets qu’elle a laissés.

Eu égard au genre, les productions des trobairitz, « troubadouresses » des 12e et 13e siècles avaient été et étaient restées exceptionnelles : littérairement, par le précédent qu’elles proposaient en inversant les rôles traditionnellement distribués entre le désirANT et la désirÉE, mais aussi statistiquement, en tant que travaux de femmes de la noblesse qui pouvaient se permettre de participer au commerce fermé des chansons, entre autres privilèges dûs à leur classe. Même Christine de Pizan (1364-ca. 1430), première écrivaine de métier d’Europe et metteuse en voix d’un sujet amoureux féminin, est restée un cas à part, comme beaucoup de briseuses de plafonds de verre. Lyon, ville de poètes et d’éditeurs, par ailleurs en contact direct avec la scène italienne (où émergent des poétesses comme Tullia d’Aragona et Gaspara Stampa), permet cette figure entièrement nouvelle d’une bourgeoise publiant des livres (des ŒUVRES, dit la première édition de ses poèmes) — en mesure, écrit-elle espièglement, de « non en beauté seulement, mais en science et vertu passer ou égaler les hommes ». Cette anomalie continue de susciter des théories réduisant « Loïze Labbé Lionnoize » à un canular de Scève et compagnie. Traitons-la ici comme une autrice de plein droit.

Labé ne se contente pas de jouer sur l’inversion des rôles traditionnels en se mettant en scène aimante d’un homme réduit au silence, elle exhibe et fait jouer l’asymétrie — par exemple, en faisant mine de railler à l’intérieur même du poème d’amour la difficulté de faire le blason d’un homme :

Quelle grandeur rend l’homme venerable ?

Quelle grosseur ? quel poil ? quelle couleur ?

Qui est des yeus le plus emmieleur ?

Qui fait plus tot une playe incurable ? (…)

Aussi bien, elle moque l’objectification poétique dont elle est l’objet en tant qu’aimée, et ses figures controuvées :

Las ! que me sert, que si parfaitement

Louas jadis & ma tresse dorée

Et de mes yeus la beauté comparee

À deux Soleils, dont Amour finement

Tira les trets causes de ton tourment ?

Ou estes vous, pleurs de peu de duree ?

Et Mort par qui devoit estre honorée

Ta ferme amour & itéré serment ?

Donques c’estoit le but de ta malice

De m’asservir sous ombre de service ?

Pardonne moy, Ami, à cette fois,

Estant outrée & de despit & d’ire :

Mais je m’assure, quelque part que tu sois,

Qu’autant que moy tu soufres de martire.

Le scandale véritable de Labé, que permet l’imagerie empruntée à Pétrarque, est surtout l’expression d’une passion féminine dévorante et sans repentir ; les formulations en sont les vers les plus célèbres de Labé : Je vis, je meurs : je me brule & me noye / J’ay chaut estreme en endurant froidure… Baise m’encor, rebaise moi & baise… J’ay senti mile torches ardantes… Tu es tout seul tout mon mal & mon bien, / Avec toy tout, & sans toy je n’ay rien… Dans le « Débat de Folie et d’Amour » qu’elle orchestre en prose, à partir d’une forme dialogue naguère affectionnée par les Rhétoriqueurs, c’est à la manière d’Érasme au service de la Folie qui rend Amour aveugle que se met toute son éloquence : « Qui eût traversé les mers, sans avoir Folie pour guide ? » Comme chez Scève, le genre amoureux et ses codes ne sont pas pris en et pour eux-mêmes, mais sont le moyen d’une scrutation du monde.

Libre des tentatives de Clément Marot et Jacques Peletier de fixer le schéma de rimes du sonnet, qu’elle mitige d’influence italienne directe, autant que des prescriptions de Du Bellay qui voudrait proscrire les rimes équivoques des Rhétoriqueurs (chez Labé, espris [épris] rime avec esprit), cette poésie affiche son indépendance à l’égard des partis pris du maître Scève lui-même, en proposant, une décennie après DÉLIE, une poésie selon le goût du moment, qui pousse l’impératif de clarté jusqu’à l’éblouissement, et pour autant infiniment créative et joueuse.

L’idée même d’une Pléiade alternative qu’on pourrait voir se dessiner ici, dans cette série de sept qu’il est maintenant temps de clore, ne ferait que perpétuer la sottise d’une constellation fermée d’astres flamboyants. La richesse de ce qu’on a pu appeler la Renaissance ne se laisse pas réduire à quelques têtes d’affiche : nous avons peut-être un peu touché du doigt le fait que, de la même manière qu’elle ne s’est pas séparée de la fin du Moyen-Âge par une rupture franche, la Renaissance s’est constituée par continuums géographiques, milieux, échanges interpersonnels et interdisciplinaires, qui ont permis les positionnements et les singularités. En évoquant quelques noms, on ne fait que prélever des échantillons. Cette évidence pour rappel de tout ce qui nous échappe ici, nous seulement à cause de l’immensité du corpus, non seulement même parce que toutes les œuvres n’ont pas survécu, mais aussi parce qu’elles n’ont pas toutes été écrites. Au nom des oubliées et oubliés, des inconnues et inconnus, je convoque pour finir Pernette du Guillet (~1518-1545), étoile filante de l’école lyonnaise dont nous ne savons pas grand-chose, et dont on parle généralement surtout au titre de sa relation amoureuse supposée avec Maurice Scève. Sa poésie a pourtant été mise en musique plusieurs fois de son vivant déjà, et le volume posthume de ses RYMES réédité plusieurs fois dans les années qui ont suivi.

Les 73 poèmes de du Guillet qui nous restent, qui forment un précédent essentiel dix ans avant la publication des ŒUVRES de Louise Labé, ont suscité des lectures contrastées, et on a pu y voir tantôt un ensemble cohérent quoique inégal, tantôt une forme de journal du développement de la jeune poétesse, qui se détache progressivement du modèle de Scève pour trouver sa voie propre en combinant épigrammes (poèmes courts), chansons, traductions… et en se positionnant en discussion à la fois avec les modèles français et l’héritage de Pétrarque.

La figure de la discussion domine de fait l’écriture de du Guillet, non seulement dans ses influences, mais dans ses énoncés. Non contente de refuser par sa prise de parole même le statue d’aimée silencieuse, elle conteste aussi la position de disciple :

Si je ne suis telle, que soulois estre,

Prenez vous en au temps, qui m’à appris,

Qu’en me traitant rudement, comme maistre,

Jamais sur moy ne gaignerez le prys. (…)

Alternant points de vue masculin et féminin, elle remet aussi sur ses pieds le discours amoureux qui préfère l’amour lui-même à l’objet/co-sujet de l’amour :

A qui est plus un Amant obligé

Ou a Amour, ou vrayement a sa Dame ?

Car son service est par eulx redigé

Au ranc de ceulx, qui ayment los, & fame.

A luy il doibt le cueur, a elle l’Ame,

Qui est autant, comme a tous deux la vie :

L’un a l’honneur, l’autre a bien le convie :

Et toutesfois voicy un tresgrand poinct,

Lequel me rend ma pensee assouvie,

C’est que sans Dame Amour ne seroit point.

Dans le conflit du corps et de l’âme, le trivial d’une relation à négocier se mêle sans solution de continuité avec un genre à réinventer :

Le Corps ravy, l’Ame s’en esmerveille

Du grand plaisir, qui me vient entamer,

Me ravissant d’Amour, qui tout esveille

Par ce seul bien, qui le faict Dieu nommer.

Mais si tu veulx son pouvoir consommer :

Fault que par tout tu perdes celle envie :

Tu le verras de ses traictz se assommer,

Et aux Amantz accroissement de vie.

Au moins subjectivement, il m’est difficile de lire Pernette du Guillet sans y associer les épigrammes qu’écrira trois siècles plus tard Emily Dickinson, autre poétesse à la carrière posthume :

A Charm invests a face

Imperfectly beheld—

The Lady dare not lift her Veil

For fear it be dispelled—

But peers beyond her mesh—

And wishes—and denies—

Lest Interview—annul a want

That Image—satisfies—

Dickinson a lu et recopié la poésie des poètes métaphysiques anglais du tournant du 16e siècle, en particulier George Herbert (continuateur de l’inspiration psalmiste et protestante de Marot), et dans ce soin de la miniature rythmée, d’une discussion allusive où les petites choses se mêlent aux grandes par l’usage de la capitalisation, quelque chose se préserve, tradition secrète d’une écriture équivoque qui refuse la réduction à l’intime et pourtant ne se soucie pas de faire Grande Chronique — dans une équation que tient le serrage de la forme. Cette poésie musicale, souvent ludique, a pris différentes formes parallèlement aux formes institutionnalisées qui appauvrissent notre langage et nos expériences, et il importe d’en chérir les apparitions, dont le 16e siècle, au seuil de l’invention d’une France centralisée et homogénéisée également linguistiquement et littérairement, aura parmi d’autres regorgé.

J’ai dit !